Marker located on Service Road, East Highway 80.

Living with only 13 inches or rain each year, it may be hard to imagine that Ector County was once the bottom of a deep stagnant marine basin full of organisms. But that was about 225 million years ago when conditions were right to create one of the world's largest reservoirs of oil and natural gas right here in Ector County. It took until 1929 to discover the riches under the ground, though people from as far back as 10,000 years ago have tried to make the most of what they could find on top of our county's hidden treasure.

Ten thousand years ago herds of bison, camel, horses and mammoths, all extinct by 5,000 B.C., thundered across Ector County. They were hunted by groups of nomads known as the paleo-Indians. although not many artifacts have been found from this time period, we do know that they made beautiful and deadly stone points which were attached to spears and thrown with the aid of an atlatl. Archaeological research has also revealed that Ector County's paleo-Indians lived in groups to insure better hunting results. They gathered fruits, nuts and seeds of wild plants to supplement their diet. Little else about their lifestyle has been unearthed.

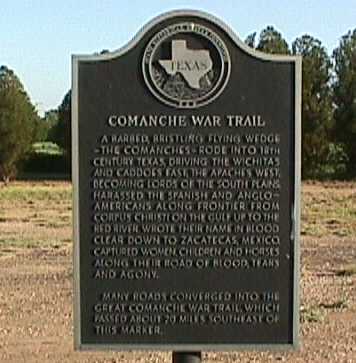

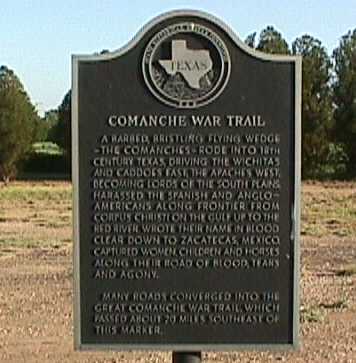

Better known native people are the nomadic Comanches who gained control of West Texas from the Apaches around 1700. What has become known as the Comanche War Trail, originally began as an animal trail that became an efficient pathway to follow the migrating herds of buffalo. The trail brought thousands of Indians through our area.

The Comanches were fierce warriors, excellent hunters and skilled horsemen. One observer wrote that Commanche warriors would hang over the side of their horses with just a foot across its back and ride at full speed, shooting arrows under the neck of the horse to keep their own body protected. Indeed Comanches have been credited with being able to shoot 20 arrows in one minute during their hunting and raiding expeditions.

The Comanche braves have been described with long hair. They apparently plucked their eyebrows and facial hair. Through their pierced ears they wore shell earrings and rings of brass and silver. Their women kept their hair short and painted their faces in brilliant red, oranges and yellows.

Archaeological evidence showed that they made jerky and pemmican. They did not grow their own corn, but they traded for it to supplement what they could hunt and forage. Their diet consisted primarily of buffalo, beef, plums, grapes, berries of all types, prickly pear fruits, and nuts.

Once the buffalo and wild horses had been systematically decimated, the Comanches's way of life likewise ended and the last warring tribe gave up in 1875. At the height of their strength the Comanche territory ranged from the Rocky Mountains to the Mexican Border.

Marker located on Service Road, East Highway 80.

Even before the Comanches claimed West Texas, Spanish explorers were already familiar with the Llano Estacado-the Stalked Plains- and with Ector County. By 1684 three important Spanish expeditions had traveled through our area. Their written accounts described Ector County's lush grasses but the lack of people to convert, easily available water and typical riches delayed any permanent settlement in the area until nearly 200 years later.

In 1849, gold fever brought Captain Randolph E. Marcy of Fort Smith, Arkansas through our area and rekindled the interest in its development. Marcy had been ordered to find the shortest route to the gold fields of California. His expedition eventually brought him east from Monahans sandhills through Ector County, across Midland County to Mustang Spring, just west of Stanton. His work served as a guide for Captain John Pope of the Topographical Engineers of the US army who came to West Texas in 1854 and is credited with bringing the railroad through Ector County.

Pope's orders were to find a suitable route for the Pacific railroad and locate available water sources along the way. In his report to Jefferson Davis, then U.S. Secretary of War. Pope stated that around what is Ector County "artesian wells could be built" and further that the rail road "must pass through the Stalked Plains." His conclusion was based on the fact that the land was flat and easy to lay track on, water was accessible though not plentiful, and mesquite roots could provide enough fuel to support the railroad workers. His report was substantiated by Colonel William Shafter of Fort Davis who also had scouted the area.

The successful cattle drives previous to the railroad's eventual presence in West Texas provided reliable evidence that the area could not only sustain Indians and the army but also a very lucrative "industry" too. James Patterson drove herds across our area repeatedly to the markets in New Mexico, as did John Chisum who is credited with opening up the Pecos West area for cattle ranching. In fact, although the Goodnight-Loving Trail did not pass directly through Ector County, the cowboys on the trails must have become familiar with our county when they were forced to look for lost livestock.

Thanks to Pope's recommendations and careful consideration, the railroad did choose a route that came through what has become Ector County. For thousands of years, our area has been a good place to be. The Native Americans knew it and returned century after century, the railroad developers knew it and spent a small fortune in developing a community called Odessa and we still know it today.

Courtesy: The Flavor Of Odessa, 1891-1991;

Editor:Ann Sherburn.

The Heritage of Odessa Foundation.